| Business Editor for The Spinoff

The numbers bandied around are staggering. A 2013 report by BERL for Te Puni Koriri has a page of ‘headlines’, but they are really a kind of list of boasts: gross domestic product (GDP) from Māori economy producers totaling $11 billion, an asset base of $42.6 billion (up 15.4% on 2010 stats), and $1.8 billion earned in the primary sector. The report notes that primary sector GDP contributions mostly came from trust, incorporations, and other collectively-owned Māori organisations, or from the groups we often think of when the Māori economy is mentioned – those heavy hitters like forestry, fishing, and tourism.

Keep reading and another picture emerges. There’s $1.3 billion earned from manufacturing, and $670 million from the construction sector, and that’s before even mentioning transport. And in these sectors, it’s not so much the iwi groups with settlements to play with – these sectors’ GDP contributions are “mainly from enterprises of individual Māori employers and self-employed Māori”, the report finds.

Former Māori development minister Te Ururoa Flavell said this year, “the Māori economy is thriving with our people and enterprises holding significant assets in our primary industries – including in farming, forestry and fisheries. [But] we can’t just focus on our large enterprises. We need to pay special attention to our small businesses to ensure they have every opportunity to grow our economy and support our people”.

Statistics New Zealand data from 2015 found 660 significant Māori small-to-medium enterprises, with about 1 in 5 exporting to offshore markets. Entrepreneurship and interest in small business appears to be growing, with the number of self-employed Māori on the rise. The latest available data from MBIE shows 10% of Māori are small business owners, being either self-employed or employers.

In 2013, BERL found self-employment among Māori had risen from 6% in 2006 to 6.3% in 2013. The economic researcher found “the higher percentages of Māori employers and self-employed… suggest that Māori are becoming increasingly more important in the New Zealand entrepreneurial scene”.

EBONY WAITERE. (SUPPLIED)

It pinpointed the rise of small business ownership and self-employment as a response to the global financial crisis. Can’t find a job? Set up a company or contract instead the BERL report suggests. So what sectors are all these small businesses (or 14,900 self employed) in? Not all too surprisingly, construction takes a decent slice with 2,600 Māori, followed by transport with about 800.

But the businesses often attracting interest and hype are not those in the trades, and they are often ones which imbue something particularly Māori in how they operate, or even the products they make. For example, Huia Publishers executive director Eboni Waitere says the publisher couldn’t unwind being Māori from its identity; it just is and always has been.

How does being a Māori business impact their decisions? It’s pretty simple, Waitere says. “Sometimes our published works may not have very wide appeal, but from our perspective, they are important pieces of work… They may not have a huge return but we know they are important to us.”

This focus makes sure Huia is helping Māori tell Māori stories, rather than other people of other races and ethnicities telling their stories for them. Being a Māori business also shapes its structure, Waitere says, down to she and Brian Morris sharing the same job of executive director, and “working together, male and female”.

Waitere says often the conversation about the Māori economy is fixated on treaty settlements and the primary sector, which is a big part of it, but not the whole picture. “Huia has been around for 20 years,” she points out.

Huia is as old as some of the fisheries settlements, she says, but has been operating in the tumultuous publishing world, with a steely focus on bringing out Māori writers and voices.

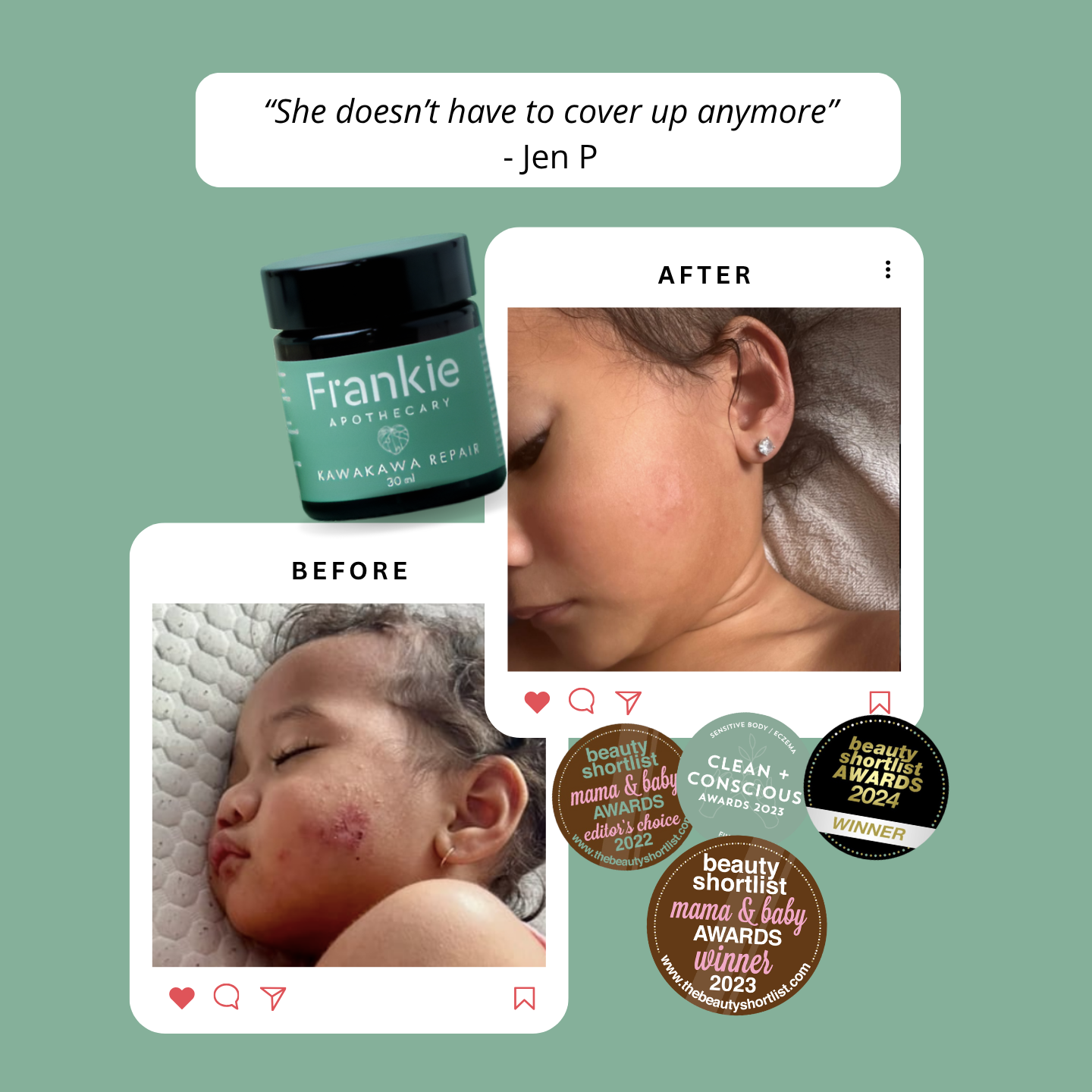

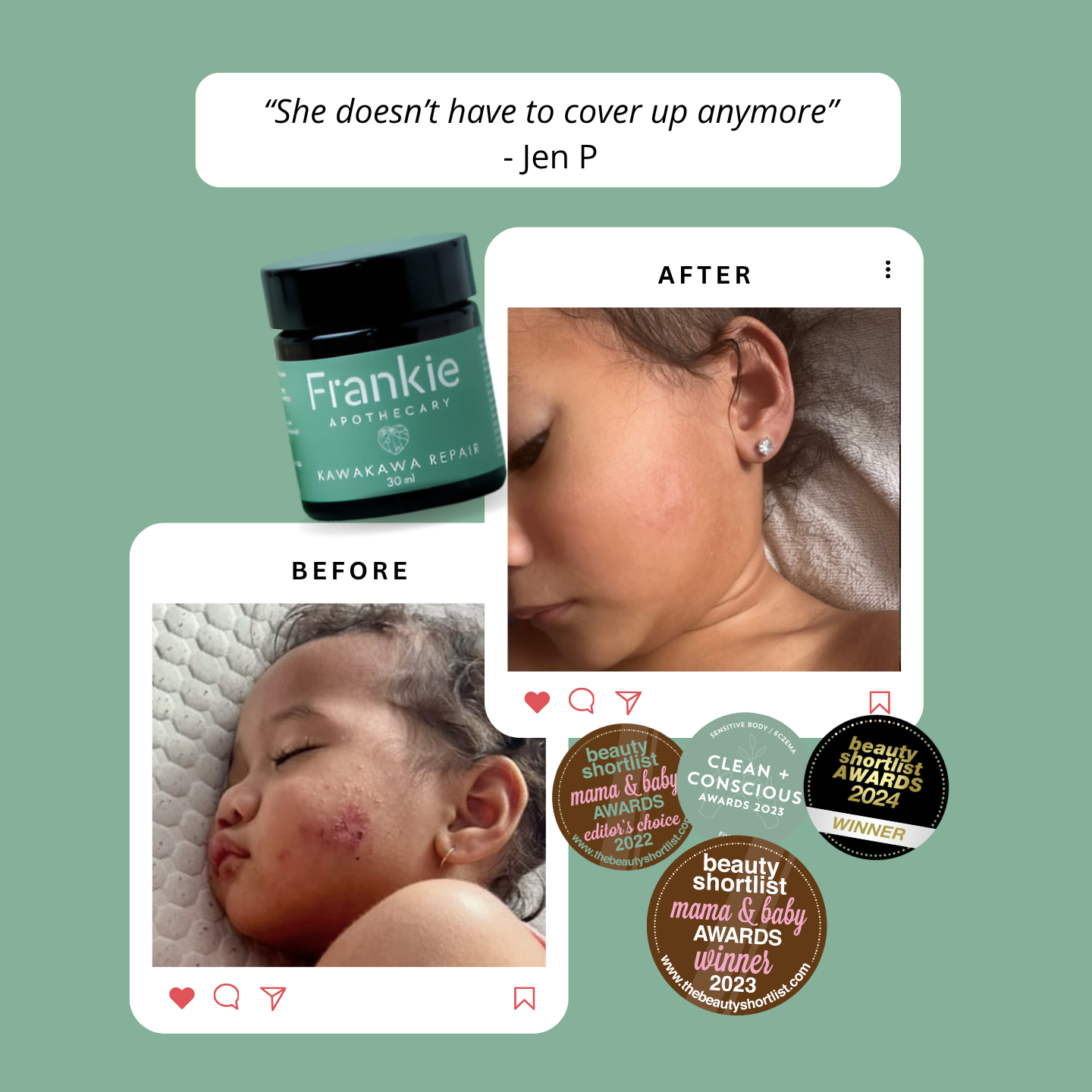

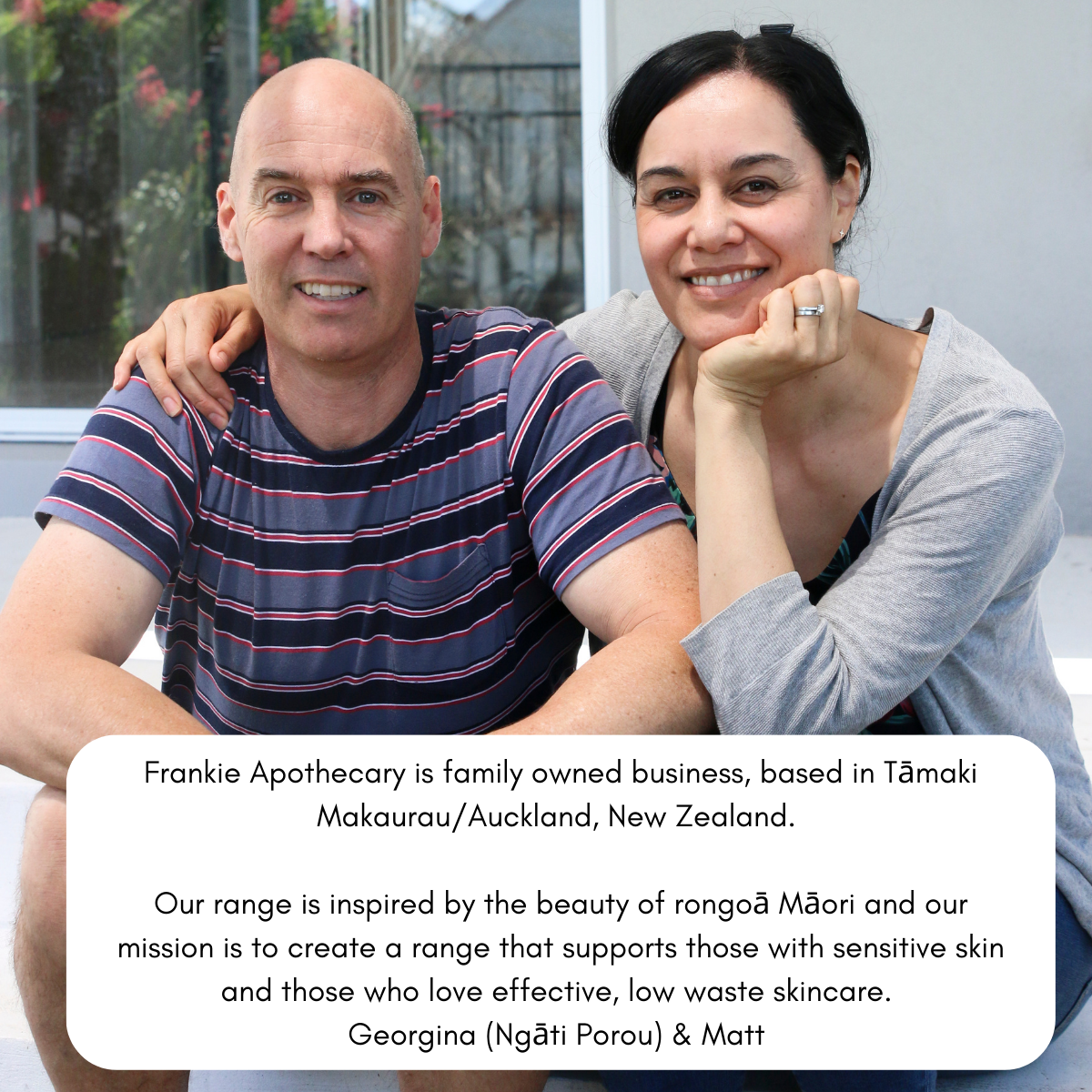

Also uniquely Māori are the traditional herbs that are drawing new appreciation as products for skin ailments, and with the right marketing could bring global interest and dollars to the Māori economy. Michele Wilson, the Frankie Apothecary founder, certainly hopes so. She has seen her Kawakawa Balm become the linchpin product in a now flourishing skincare business sold at high-end children’s retailers like Nature Baby and Huckleberry.

It’s a compelling origin story too. Wilson’s daughter was suffering from severe eczema, so she spent hours researching treatments before looping back to an ingredient she’d known about all along: kawakawa. Wilson says that the first kawakawa cream she made cleared up the eczema within a week. Since then, she has had one of those meteoric rises that would make a good movie – or just a viral hit.

Frankie was a coveted Oh Baby Award finalist before she had really set up the company. “I wasn’t even a business then,” she says. “It was never a business, I was just making these products for my family.”

It is a family business, with the Te Atatu mum the only official staff member. The Tainui and Ngāti Paoa woman collects the plants from a family farm in Mangawhai with all kawakawa harvested regenerated – it’s critical for Wilson she follow tikanga; only taking what is needed, and ensuring it is replaced.

She is at pains to make clear she is not practicing rongoā Māori, traditional Māori healing, and says she has been tutored. But her tutors are the real experts. Wilson says she sticks to Māori protocol, but says her products are not part of this practice – they are simply products that contain some of the same active ingredients.

For Wilson, not only are Māori ingredients and shared cultural knowledge at the core of her business, she’s also gone on a personal awakening, taking in her ancestry and heritage. Her family left the Waikato in the 1970s, migrating to Auckland City. While her family held onto te reo, it was inevitable some connections with her roots were lost after her whanau moved away from the marae. “I felt a disconnect with that side of me,” Wilson says.

She believes her business has been a calling that has ultimately connected her with her roots. “I am just on this journey,” she says.

Frankie Apothecary has just received SPF50 certification for a kawakawa sunblock, but Wilson says she’s happy growing at her pace, at her capacity. She has no debt, no overdraft, and has been pouring profits back into the business, giving Frankie a solid start at achieving a chance at joining Huia as a longstanding, successful Māori business.

Because they need to leave a legacy, BERL says. “The success of these recently established individual entrepreneurs will play an increasing role in determining both the nature and magnitude of the future contribution of the Māori economy.”